Nobody ever died of laughter.

– Max Beerbohm

Aside from having a little giggle at his expense, what can caricature and cartoons tell us about how John Singer Sargent was perceived in his own time?

Humour is an easier, more socially acceptable way to critique the absurdities of modern life, it's strange customs, mores and interactions - or as Henry James noted an 'oddity that was strangely compatible with the dominion of convention.' As the spoonful of sugar in the medicine, comedic artists and authors in the nineteenth century used their platforms to address the ever shifting standards by which propriety was made, discussed and, in many cases, ignored altogether. Montagu F. Modder (a possibly satirical name in itself) called du Maurier's Punch a 'watchdog of society', while Cornhill Magazine noted on the death of popular Punch illustrator John Leech that it was a format which 'enabled him to play directly, and without intermission, on the hearts of a whole nation.' Social consumption of media is just that - a conscious and subconscious 'taking in' of subliminal messaging that sticks in the brain and wrestles itself free in action - but in the case of satirical cartoons, the call to action for betterment is a little less subtle.

If the concept of the satirical cartoon is to not only 'poke fun' at society but also to educate, cultivate dialogue and, maybe in some cases, institute change - what exactly can be learned from the incessant rounds of mockery that Sargent suffered at the hands of Punch and beyond? Since the early years of his career in the 1880s, all the way to his work as a official war artist in WWI, public and private cartoons have been a staple of the social digestion of Sargent's art and character.

Clearly a man who reads Baudelaire.

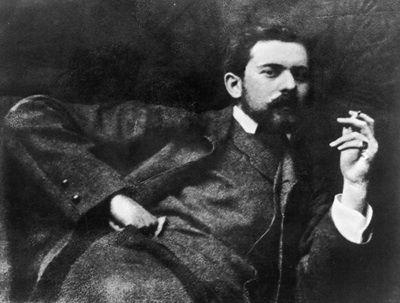

First, there is Sargent, the physical presence of the man himself. Though he appeared lean and bohemian in his early photographs (especially the delectable ennui of his cigarette smoking lean of this photo from the early 1880s - straight out of Paris Vogue it seems), it was quite clear from the cartoons that his increase in celebrity came in direct proportion to the increase in his waistband. As his head got smaller and his body got bigger, it seemed that the cartoonists were using the physical body of Sargent himself to symbolically reflect the growth of his social status. Sir William Rothenstein made this direct connection between Sargent's prodigious appetite and his insatiable artistic productivity:

"I felt that something essential was lacking in Sargent. He was like a hungry man with a superb digestion who need not be too particular about what he eats. Sargent's unappeased appetite for work allowed him to paint everything and anything without selection, anywhere at any time... [In the mid 1890s Sargent] still came sometimes to lunch at the Chelsea Club,but complained that he couldn't get enough to eat there. So he often went to the Hans Crescent Hotel, where, from a table d'hôte luncheon of several courses, he could assuage his Gargantuan appetite."

He was like a hungry man with a superb digestion who need not be too particular about what he eats.

– Sir William Rothenstein

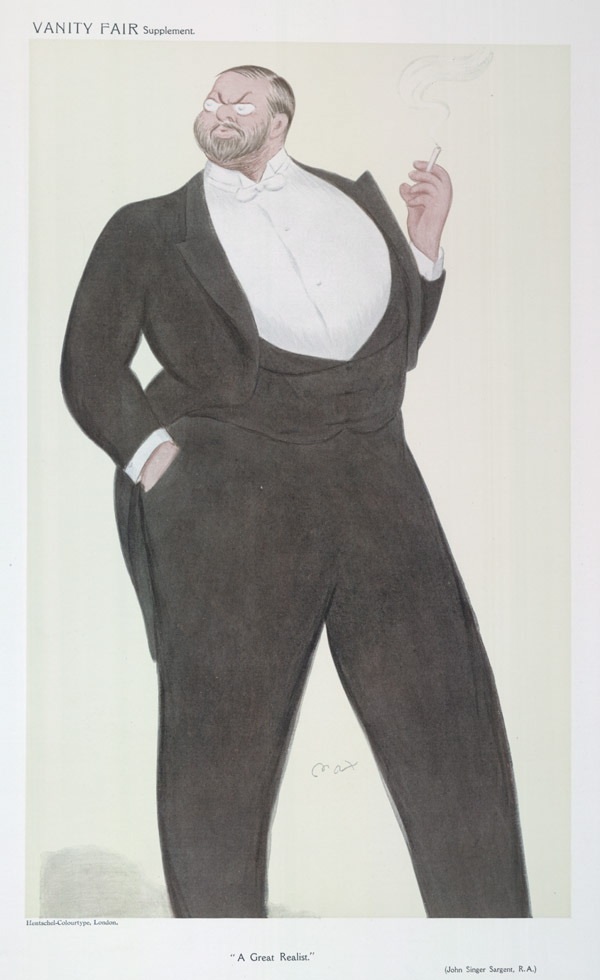

Dapper Rotundity in Vanity Fair, 1909

J.E. Blanche also noted: 'The Van Dyck of Tite Street had to make appointments six months or a year ahead with Royal Highnesses just as occupied as he. During the season, at the groom grill of the Hyde Park Hotel, he devoured his meals and gulped down his wine, [with] his watch on the table in front of him...There was just half an hour for recharging the motor, for filling it with life-giving spirit, between the morning sitting and another, sometimes two, in the afternoon. Stuffed with food, smoking Havana cigars as large as logs, with bloodshot eyes, puffing, he looked through The Times. There was about him something of a townsman - of Walt Whitman and a City man - though without the latter's desire for comfort'.

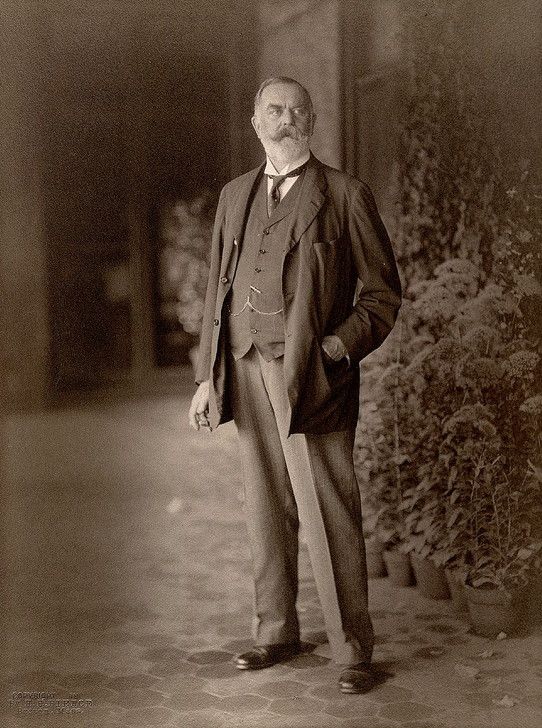

For Blanche, Sargent used his heavy stature, stuffed to the gills with fine food, wine, and cigars, as a veritable energy source for his prolific painterly outputs. The more people he painted and wealth he amassed, the larger his waistband became. These images, however, were less than kind. Contemporary photographs, especially this one taken the year before his death in 1925, show that though rotund, Sargent balanced his weight with appropriate height. But, there is something to be said for Sargent's mocking rotundity and his 'zest for life' both artistically and physically.

Stuffed with food, smoking Havana cigars as large as logs, with bloodshot eyes, puffing, he looked through The Times.

– Jacques-Emile Blanche

Image by Henry Havelock Pierce, 1924

Sargent seemingly used his gargantuan appetite to fuel another aspect of his 'caricature' - that of his seemingly mad-dash artistic practice. Sargent was known to have painted in a method called 'tonal mapping' which he learned from his Parisian painting instructor Carolus-Duran. R.A.M. Stevenson, cousin to the famous Robert Louis, discussed this method in depth in his The Art of Velazquez of 1895, where planes of light and shadow were mapped out in a sort of rough sketching method according to tonal value, then blended together to form the finished picture. 'The main planes of the face must be laid directly on the unprepared canvas with a broad brush... They were painted quite broadly in even tones of flesh tint, and stood side by side like pieces of a mosaic, without fusion of their adjacent edges.'

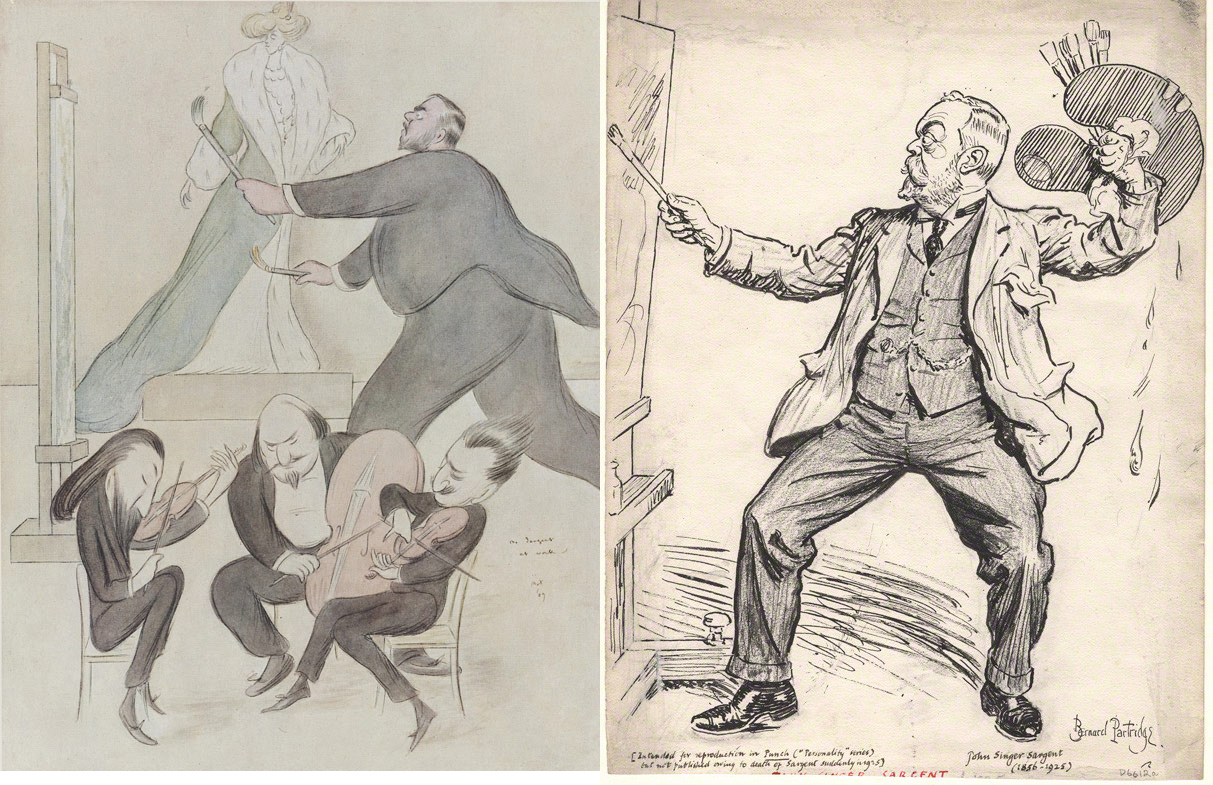

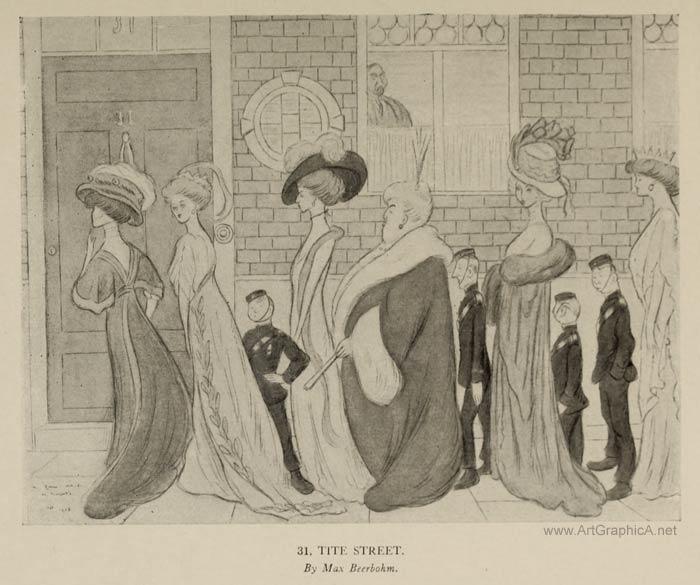

Because of this method of quick 'sketching', Sargent was often witnessed running back and forth to the canvas to examine how the planes of light and shadow that he mapped up close blended together to form the finished image when viewed at a distance. Edmund Gosse notes this mad dance of Sargent's while he painted Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose at Broadway in 1885, while Max Beerbohm gave Sargent's energy a specifically 'musical' tone in his cartoon of such a method of 1907.

Instantly, he took up his place at a distance from the canvas, and at a certain notation of the light ran forward over the lawn with the action of a wag-tail, planting at the same time, rapid dabs of paint on the picture, and then retiring again, only, with equal suddenness, to repeat the wag-tail action. All this occupied but two or three minutes, the light rapidly declining, and then, while he left the young ladies to remove his machinery, Sargent would join us again, so long as the twilight permitted, in a last turn at lawn tennis. - Gosse (Charteris 74-75).

It was likely due to this 'mad dash' method that enabled Sargent to produce a staggering number of portraits per year. In the 1890s at his height he was noted to have produced 14 full length portraits a year, which were charged at around £525 each (or roughly £32,000 in today's money).

Max Beerbohm (1907) & Sir John Bernard Partridge (1925).

All the great ladies line up to be 'Sargent-ed'. Max Beerbohm, c. 1910.

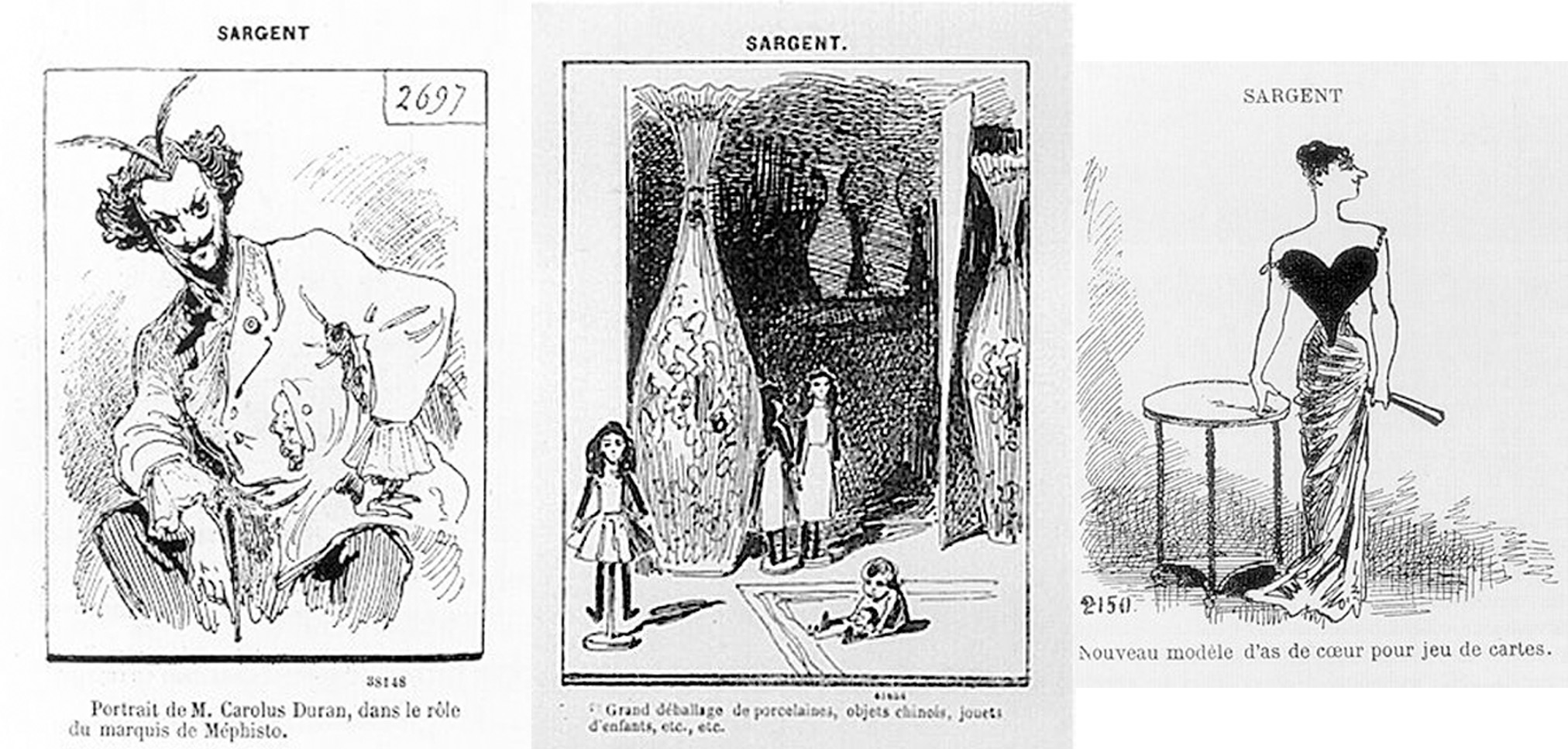

The prolific nature of Sargent's person and artistic practice meant that there was much fodder for caricature, particularly in the early years of Sargent's career. The French press found considerable humour in Sargent's avant-garde style and clientele when their portraits began to emerge in the Paris Salon in the late 1870s. While critical reception was general positive, Sargent's pursuit of more eccentric compositional and stylistic elements (elements I argue are significantly Aesthetic in nature) left him prime for ridicule. A collection of cartoons from Le Journal Amusant and Le Charivari, depicting Sargent's portraits of Carolus-Duran (1879), Portrait d'Enfants or The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit (1883) and Madame X (1884) all indicate that the French critical reception was struggling to comprehend Sargent's bold and 'curious' takes on his Old Master influences, blending a Velasquez aesthetic with Impressionist and contemporary modes of quick paint, simplistic lines and modern pigmentation.

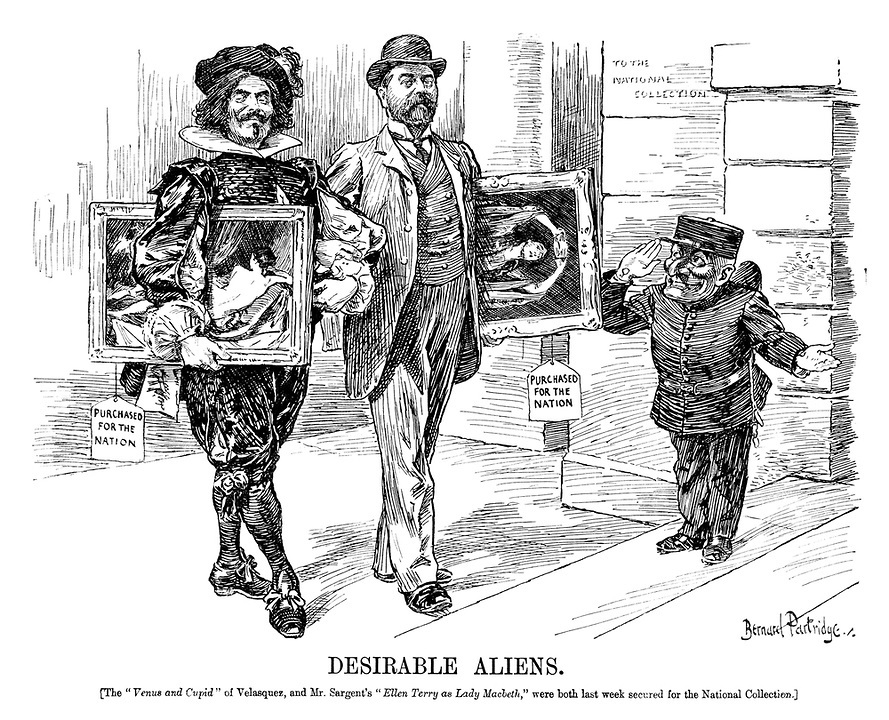

While a very long and entire blog post could be written discussing Sargent and the 'Velazquez Aesthetic' (which coincidentally will be the subject of one of my upcoming publications), the critical link between Sargent and the Old Master was one that continued well into the 'cartoonery', even late into his career. In a Punch cartoon from 1906, Sargent is seen carrying his portrait of Ellen Terry as Lady MacBeth while walking hand in hand with Velazquez, who also carries the Rokeby Venus. Both march boldly into the National Gallery, where their works would stand in perpetuity with the likes of Reynolds, Gainsborough and Turner. The cartoon makes no distinction between the fact that the Venus was bought for the nation through the National Art Collections Fund, while Lady Macbeth was donated by Sir Joseph Duveen. Indeed, the source of the works appears irrelevant to the fact that these two illustrious additions to the national collection came from 'desirable aliens', or painters who were not British. So while Sargent seemingly has reached the same stature as the great Old Master - unlike the criticism in the press early in his career, which implied him to be a type of Velasquez 'pretender' - he is still ostracised for his American parentage. Sargent's 'nation', as implied by the 'alien' epithet in this cartoon, was an often contestable aspect of his career as a painter. British, French, American - even to this day, art historians and critics struggle with how to accurately define and place an artist like Sargent, even though he remains revered and hallowed in the canon.

Much of this, however, was purposefully done. Throughout his life Sargent refused on multiple occasions any offer to 'become an Eng-lish-man', as Whistler jovially wrote to him in 1894, even refusing an offer of knighthood in 1907 in order to keep his American citizenship. Replying to Whistler, he wrote:

'As for the question of nationality, I have not been invited to retouch it and I keep my twang. If you should hear anything to the contrary, please state that there was no transaction and that I am an American.'

As evidenced by his steadfast belief in his own nationality, Sargent seemed to stride comfortably, as depicted in this cartoon and implied in many others, through the various attempts to mock or criticise his more 'alien' approaches to his person, his life and his art. Be it rotund, eccentric, or 'alien', these cartoons highlight Sargent's energy, forward thinking and dazzling talent as an artist - characteristics we are still perhaps 'having a laugh at' to this day.

Tell me one thing only – did you, in the face of great temptation, chuck up t'other nation, to become an Eng-lish-man?

– J.M. Whistler to Sargent (20 January 1894)