Whenever I manage to attend a new Sargent exhibition, I ask a very simple question - which side of Sargent are we seeing?

–

There are two conflicting frames of mind about Sargent in academia. The first, cultivated by modernist critics like Roger Fry and Walter Sickert in the early years after his death in 1925, is that Sargent is distinctly ‘of his time’. While beautiful, he is vapid and overly luxurious - an old relic of an imperialist age that will add nothing new to the timelines of the history of art. While this sentiment has been slowing dissolving in the past twenty or so years, bolstered by recent blockbuster exhibitions - like the Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends at the NPG in 2015 - there is still a creeping sentiment that Sargent is too beautiful to be taken seriously (e.g. see The Telegraph’s review - ‘Too Pretty for his Own Good?). Recent art historians, myself included, have attempted to push back against this by fostering ground for new, more innovative scholarship - engagement with Sargent’s queerness, for example, or his attraction to French decadence. It has taken a good deal of time to try to slowly melt both the progressive and conservative approaches to Sargent’s work into a framework that continues to say something new or valid for our evolving understanding of Victorian visual culture. In this light, whenever I manage to attend a new Sargent exhibition, I ask a very simple question - which side of Sargent are we seeing?

As a Sargent scholar, I confess that tend to review Sargent focused exhibitions with some trepidation due to issues with the impartiality of my own eye. I’ve studied and looked at and talked about Sargent with some consistency for nearly six years now. So attending a new exhibition, like the recent Sargent: The Watercolours at Dulwich Picture Gallery, I always consider my own Sargent weariness. I do not always experience the ‘awe’ that other patrons around me do at his works, but that is because many of them I have seen, often, in my travels. This is most obvious in my conversations with others who have managed to see it - their exclamations of ‘wonderful’ and ‘delightful’ fill me with a sense of sadness - am I too close to the subject to ever really feel that way again? Portraits of Artists and Friends managed, in some places, to move me to almost tears. Needless to say, I have both high and low expectations.

The general consensus of the Dulwich exhibition is that it is a masterful, vibrant, and dazzling display of around eighty of Sargent’s little displayed jewel watercolours. Titled as the first major exhibition of Sargent’s works in this genre in the UK in nearly a century, it is a promising approach to an aspect of his oeuvre that is not often discussed, picking up on a time period in his career after he had sworn off major portraiture in 1907 to focus on the pleasure that comes from a wealthy man’s hard earned retirement. Pleasure is a key word here - these are images that were not usually intended for display, but were done for Sargent’s own personal exploration, like vacation photographs you take to remember and would probably never show anyone. Dulwich, in their exhibition materials, does not attempt to push back against this view of pleasure - the plaques echo the term ‘dazzling virtuosity’ I’ve seen, ad infinitum, in Sargent secondary literature. We are to be dazzled, that is clear, but are we to learn?

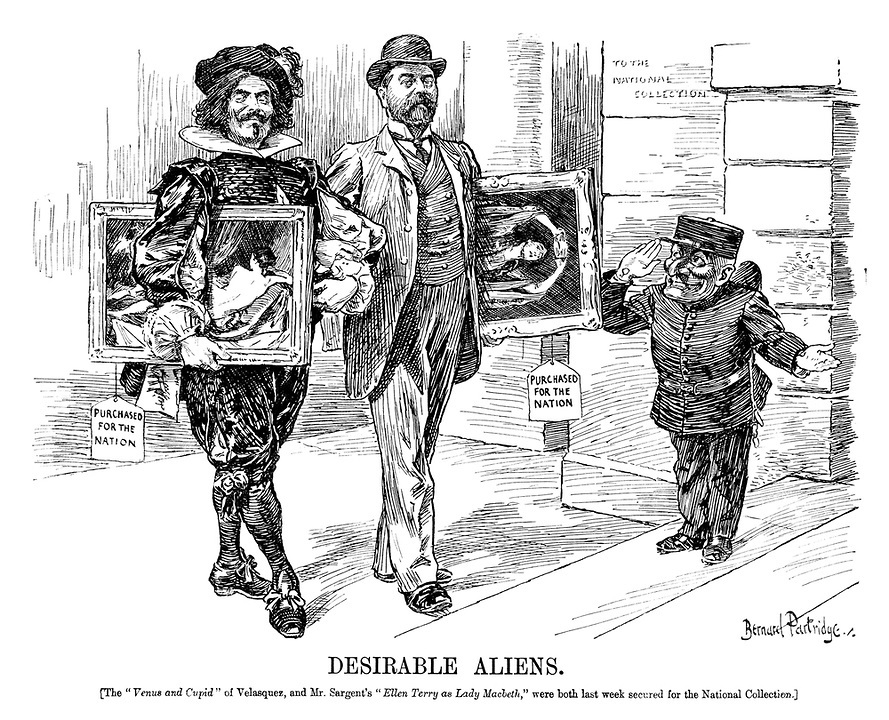

There is, first, something to be said about the decision of location at Dulwich. Outside of the more easily accessible central London galleries, Dulwich is a museum that seems initially at odds with a Sargent display. Housed in a Georgian building, the collection at Dulwich is focused mainly on European Old Masters, cultivated from a collection that was originally crafted with the intent that it would become the royal collection for the King of Poland, Stanislaus Augustus - a dream dashed by the country’s annexation in 1795. Sargent seems almost garishly modern by comparison, but upon further thought, I saw the choice of location not as antagonistic to Sargent, but as a subtle nod to Sargent’s eternally discussed status as a modern ‘old master’ - he was called the ‘Velasquez’ and ‘Van Dyck’ of his day - and after some consideration, I felt the exhibition strangely at home in a place surrounded by Gainsborough and Velasquez, even if the exhibition materials itself did not laud the connection between the two bodies of work.

Sargent & his 'twin'

But while this aspect of its location was notationally relevant to Sargent, it does make a very distinct statement regarding perception and audience. The overall clientele was older, predominantly white, and wealthy, in keeping with the gentrified aspect of Dulwich as one of London’s wealthier boroughs. This observation immediately put me in the frame of mind that this exhibition, even before entering it, was not one that was looking to innovate or make Sargent more accessible to a younger, more progressive audience. Rather, it would seem to uphold a sadly repetitive status quo of Sargent’s role, as one critic pejoratively put it, as one who ‘sold himself to the Duchesses’.

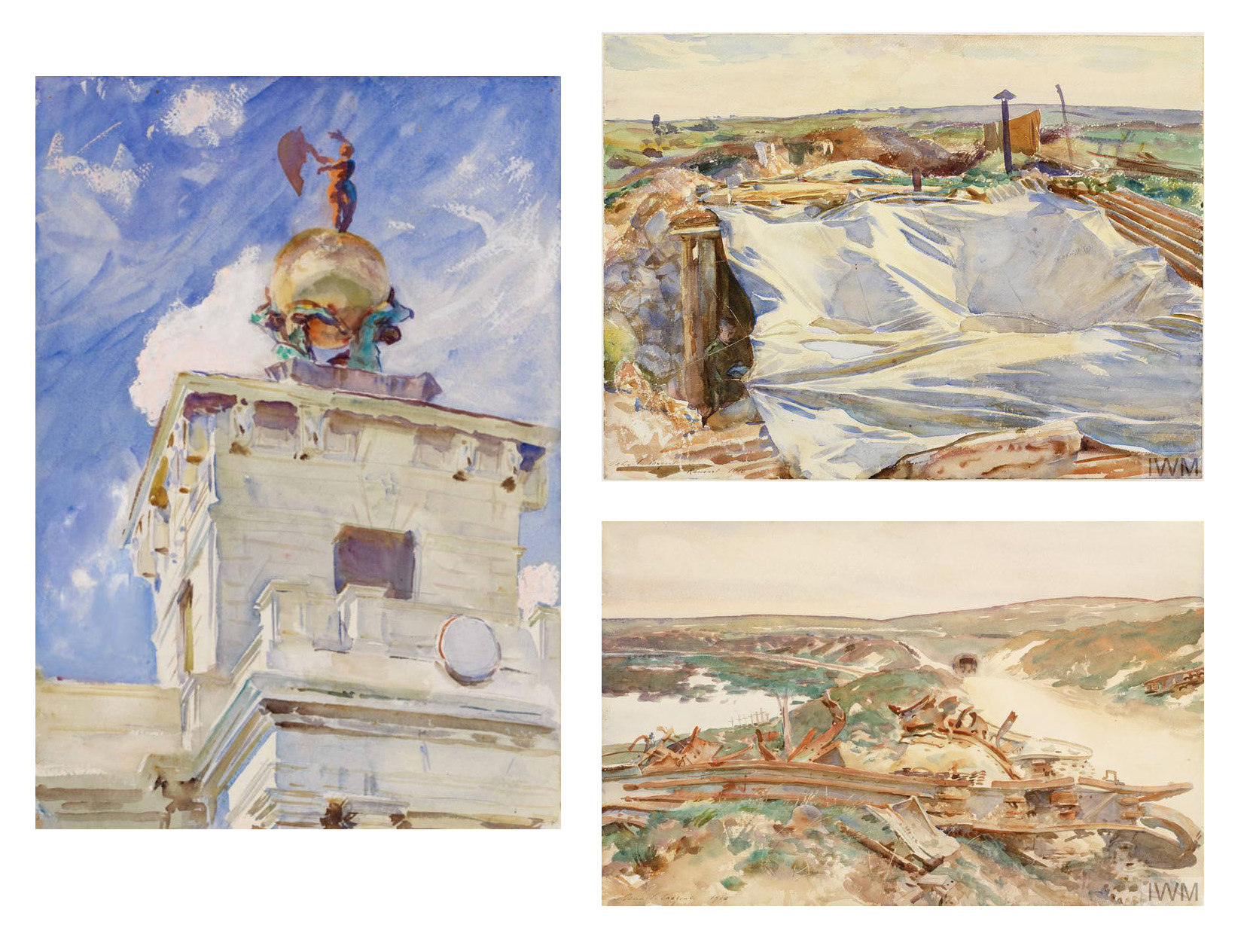

The exhibition itself did little to negate or confront this stagnant view of Sargent and his work. The first room, ‘Fragments’, contained many of the larger showpieces, notably Spanish Fountain and Venice: La Dogana. I felt shock, at first, upon entering. At one moment I was swimming in the muted tonality of British and Spanish Old Masters, only to be blinded by what I would call Sargent’s high sense of ‘dramatic chromatics’. It is a kind of brightness of colour that many found 'perverse' when the Impressionists introduced it in the 1860s, and the transition from the 'outside' to the 'inside' of the Dulwich galleries that makes you see why. But once the adjustment to the colour faded, I felt quiet introspection and a slight sense of disappointment creep in. What particularly struck me in this room was the display of some of his WWI watercolours brought over from the Imperial War Museum. They seemed vacantly luxurious in the face of the subject matter, echoing The Athenaeum’s 1919 review of Gassed that it is nothing but a ‘Bowdlerism of horror’.

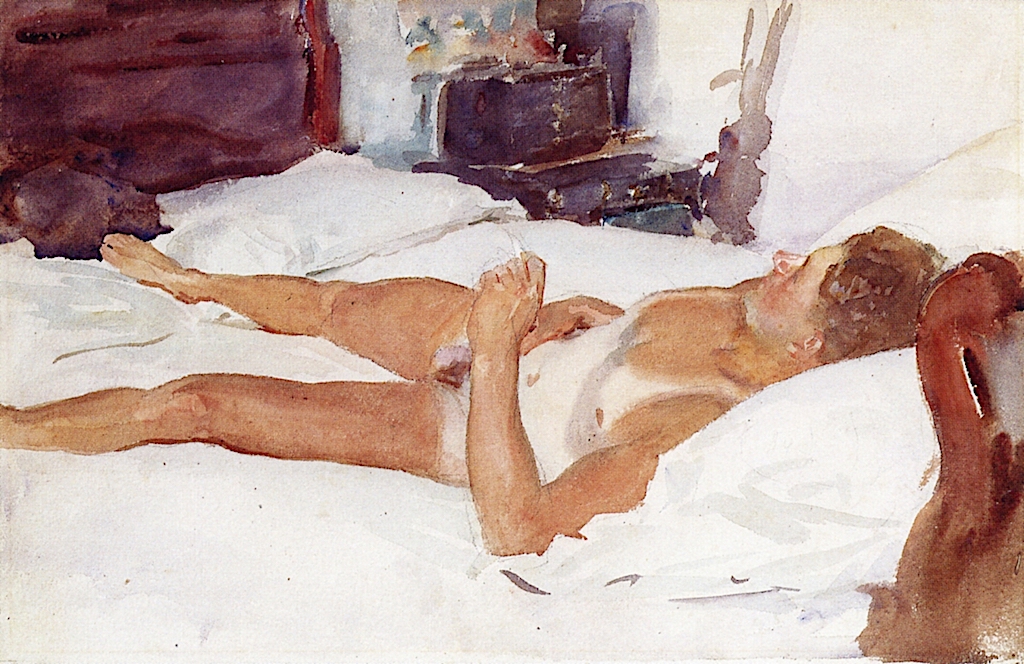

The next four rooms repeated the theme of ‘cities’ and ‘landscapes’ twice over, and in all honesty, outside of the particularly fresh and modern On the Sands of 1877, when Sargent perhaps still had something to prove, there was little of note for me in these rooms. I trudged silently until I hit the last room ‘Figures’, and then found the spark of Sargent that I knew and loved. Perhaps it is the energy of individual personality which gives more of an opportunity for engagement and life, but there were many works in this room which struck me, most particularly A Bedouin Girl of 1905 (oh the blue!), Blind Musicians (1912) and especially Nude Figure Lying on a Bed (1917) - the latter of which gave me most pause.

Nude Figure Lying on a Bed was a striking way to end the exhibition. To me, it was symbolic of the quiet unspoken truths, the evocations of controversy and otherness that runs like a subtle current under many of Sargent’s works - a thread of fascination I spend much of my time attempting to unravel. Most of the exhibition focused on Sargent the cosmopolitan, of the pleasure of the world - of sun and friends and travel. Its brightness and boldness screams at you from every angle, supporting our understanding of Sargent the large bravura painter, with his big round belly and beard and mouth full of cigars. We know this Sargent, too much. But we don’t know much about the Sargent who painted Nude Figure - he’s the one I want to know about. I had to walk through the entire exhibition to find him, and it left me wanting more.

All in all, exhibitions like the Sargent: The Watercolours are an important first step in that they provide vital initial exposure to little seen works. But sooner or later, and for me that time has already come, we might begin to sour on the overt sweetness of Sargent the ‘dazzler’. In future, I would like to see more Sargent exhibitions that attempt to engage with him in more thought provoking ways. The 2006 Americans in Paris exhibition, for example, or the 2010 Prado display of The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, or the recent focus on Mrs. Carl Meyer at the Jewish Museum last year - these are all ways in which we can dissect Sargent from more engaging avenues. I still hope for the day when Sargent’s nudes become the focus of a ‘Queer British Art’ exhibition all their own, but I will not hold my breath. All in all, The Watercolours was, for me, one step forward, and maybe one step back.